Practical Polars: Code Examples for Everyday Data Tasks

TL;DR: This hands-on guide provides practical Polars code examples for common data tasks. We cover data loading from various sources (CSV, Parquet, JSON), data exploration techniques, powerful data transformations using expressions, aggregations and grouping and joining datasets. By explicitly showing the code for these everyday tasks, this guide serves as a reference for applying Polars' performance advantages to real-world data analysis workflows. Both eager execution (for interactive work) and lazy execution (for optimized performance) approaches are demonstrated, helping you leverage Polars' full potential regardless of your use case.

In our previous articles, we've introduced Polars and explored its performance architecture. Now it's time to get hands-on with practical examples of Polars in action.

This guide focuses on concrete code examples for common data tasks. Whether you're new to Polars or looking to expand your skills, these examples will help you apply Polars to your everyday data analysis workflows.

We use a set of data downloaded from the World Bank Open Data specifically via the Data 360 API. This data is made available by the World Bank under a Creative Commons 4.0 license. It's a brilliant example of the power of open data and we'd like to thank the World Bank for making this data available.

Specifically, we will be working with the World Bank Indicators dataset, which contains macroeconomic series (GDP, population, education, etc.) for every country and year. We have prepared this data in a range of different formats to demonstrate how Polars can successfully interact with different source data formats.

You can download and run the source code in this blog which is available (along with other Polars examples) in the following public GitHub repo: https://github.com/endjin/endjin-polars-examples

Before we start: what is a DataFrame?

Polars is a DataFrame library available in Python. But what do we mean by a DataFrame?

A dataframe is a two-dimensional, in memory, tabular data structure that organises information into rows and columns, much like a spreadsheet or a database table. Each column represents a variable or attribute, while each row represents a single observation or record.

In Polars specifically, a DataFrame is a 2-dimensional heterogeneous data structure that is composed of multiple Series. A Series is a 1-dimensional homogeneous data structure, meaning it holds data of a single data type (e.g., all integers, or all strings). These Series represent the columns in the dataframe.

What makes dataframes particularly powerful is that while each individual column (Series) is homogeneous and strictly typed, the DataFrame as a whole allows for different data types across its column (e.g. strings, integers, floats, dates, boolean, complex types) while still allowing operations across the entire structure. This flexibility makes them an intuitive and practical abstraction for working with the kind of structured data that dominates analytical workloads.

For Python developers, the dataframe concept was popularised by pandas, which became the de facto standard for data manipulation over the past decade. However, as datasets have grown larger and performance expectations have increased, the limitations of pandas have become more apparent.

This has created space for newer libraries like Polars to reimagine the dataframe from the ground up, retaining the familiar mental model while delivering significantly improved performance through modern design choices such as lazy evaluation, parallel execution, and memory-efficient columnar storage that take advantage of modern compute hardware.

If you've worked with pandas, SQL result sets, or even Excel tables, you already understand the core concept. Polars simply executes on it faster and more efficiently.

Developer Experience: "Come for the Speed, Stay for the API"

The Polars community has a saying: "Come for the speed, stay for the API." This captures an important truth about Polars' adoption - while performance often drives initial interest, the well-designed developer experience keeps users engaged.

Polars achieves this through:

- Consistency- methods use snake_case naming with predictable patterns

- Fluent interface - method chaining creates readable data transformation pipelines

- Error messages - clear, actionable feedback when something goes wrong

- Schema enforcement - strong typing that prevents common Pandas "surprises" that often thwart developers

- Expression system - a composable language for data manipulation

As Vink puts it: "just write what you want and we will apply those optimizations for you... write readable idiomatic queries which just explain your intent and we will figure out how to make it fast."1 This philosophy places user experience on equal footing with performance.

This is the behaviour and benefit of a well architected system and precisely why we do the yearly .NET Performance Boost posts: we change 0 lines of code and yet we still get big performance benefits from people in the core team optimising the internals.

For those who are familiar with the PySpark SQL and DataFrame API, adoption of Polars will be quite straightforward.

For those who are coming from a Pandas background: Polars has some similarities in terms of method names, but the fundamental structure of the API is different and perhaps more fundamentally Polars applies a stricter set of principles. We may cover a "Polars versus Pandas" blog in the future, if there is demand for more detail.

Setup and Installation

Before we begin, let's make sure Polars is installed and imported correctly.

We are using uv to manage our Python environment in this demo, so we have run the following command:

uv add polars

If you are using pip, the equivalent command would be pip install polars.

If you are using poetry, the equivalent command would be poetry add polars.

Next stage is to import Polars (the convention is to use an alias of pl) and check the version we are using:

# Import Polars

import polars as pl

# Check version

f"Polars version: {pl.__version__}"

'Polars version: 1.35.2'

Creating Dataframes from scratch

There are a range of other formats which are supported for creation of Polars dataframes in code, the most common one we tend to adopt is from a list of dict (or dataclass) objects as demonstrated below. This example also shows how Polars elegantly handles null values.

The creation of a dataframe in code is useful for creating test cases in unit tests and for exploring the Polars API with small "toy" datasets.

from datetime import datetime

# From list of dictionary based records

df = pl.DataFrame(

[

{'column_a': 1, 'column_b': 'Red', 'column_c': None, 'column_d': 10.5, 'column_e': datetime(2020, 1, 1)},

{'column_a': 2, 'column_b': 'Blue', 'column_c': False, 'column_d': None, 'column_e': datetime(2021, 2, 2)},

{'column_a': None, 'column_b': 'Green', 'column_c': True, 'column_d': 30.1, 'column_e': None},

{'column_a': 4, 'column_b': None, 'column_c': False, 'column_d': 40.7, 'column_e': datetime(2023, 4, 4)},

{'column_a': 5, 'column_b': 'Purple', 'column_c': True, 'column_d': 50.2, 'column_e': datetime(2024, 5, 5)},

]

)

df

| column_a | column_b | column_c | column_d | column_e |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| i64 | str | bool | f64 | datetime[μs] |

| 1 | "Red" | null | 10.5 | 2020-01-01 00:00:00 |

| 2 | "Blue" | false | null | 2021-02-02 00:00:00 |

| null | "Green" | true | 30.1 | null |

| 4 | null | false | 40.7 | 2023-04-04 00:00:00 |

| 5 | "Purple" | true | 50.2 | 2024-05-05 00:00:00 |

In the output above, you can see Polars displays the dataframe in tabular form with column names and data types displayed.

Polars implements a strict, statically-known type system. Unlike pandas, where output data types can change depending on the data itself, Polars guarantees that schemas are known before query execution. This means that when you apply a join, filter, or transformation, you can predict exactly what the output type will be independently from the actual data flowing through.

This predictability is a significant benefit for developers: if you expect an integer column and write downstream code that depends on integer behaviour, you won't discover a surprise float conversion halfway through a pipeline (as can occur with null values in an integer column).

If there's a type mismatch, Polars throws an error before the query runs, not twenty steps into your processing chain. As Ritchie Vink, the creator of Polars, puts it: "this strictness will save you a lot of headaches".

In the top left area, the "shape" of the dataframe is displayed using the tuple (number of rows, number of columns).

Loading Data from other sources

Of course, in the majority of scenarios you will want to load data into a Polars dataframe from an external datasource.

Unlike similar tools such as DuckDB, Polars does not offer a native means with which to persist data on storage. It relies on well established standards to both ingest and persist data.

We now walk through the key examples below.

Loading CSV data

One of the most common sources of data will be from Comma Separated Value (CSV) files. Here we load the countries.csv data (country metadata) from the World Bank.

Polars provides two approaches for loading CSV files. In this case, the file is small (less than 300 rows of data across 9 columns), so we load it using the "eager" polars.read_csv method. Later on this in this blog we'll demonstrate how the "lazy loading" polars.scan_csv method may be a better choice for larger data sets.

The eager approach immediately reads the entire file into memory and returns a DataFrame, which is convenient for exploratory work with smaller files such as in this use case.

You can see that it uses sensible defaults to read the header row as column names, it also infers data types from the data (we need to provide an additional hint to treat empty strings as null values to enable longitude and latitude to be treated as floating point numbers).

countries = pl.read_csv(CSV_COUNTRIES_PATH, infer_schema=True, null_values=[""])

# Display the dataframe. By default, Polars shows the first and last 5 rows.

countries

| country_code | iso2_code | country_name | region | region_id | income_level | capital_city | longitude | latitude |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| str | str | str | str | str | str | str | f64 | f64 |

| ABW | AW | Aruba | Latin America & Caribbean | LCN | High income | Oranjestad | -70.0167 | 12.5167 |

| AFE | ZH | Africa Eastern and Southern | Aggregates | NA | Aggregates | null | null | null |

| AFG | AF | Afghanistan | Middle East, North Africa, Afg… | MEA | Low income | Kabul | 69.1761 | 34.5228 |

| AFR | A9 | Africa | Aggregates | NA | Aggregates | null | null | null |

| AFW | ZI | Africa Western and Central | Aggregates | NA | Aggregates | null | null | null |

| … | … | … | … | … | … | … | … | … |

| XZN | A5 | Sub-Saharan Africa excluding S… | Aggregates | NA | Aggregates | null | null | null |

| YEM | YE | Yemen, Rep. | Middle East, North Africa, Afg… | MEA | Low income | Sana'a | 44.2075 | 15.352 |

| ZAF | ZA | South Africa | Sub-Saharan Africa | SSF | Upper middle income | Pretoria | 28.1871 | -25.746 |

| ZMB | ZM | Zambia | Sub-Saharan Africa | SSF | Lower middle income | Lusaka | 28.2937 | -15.3982 |

| ZWE | ZW | Zimbabwe | Sub-Saharan Africa | SSF | Lower middle income | Harare | 31.0672 | -17.8312 |

Loading from Parquet files

Parquet has become the interchange format of choice for high-performance analytics, and Polars is designed to take full advantage of its characteristics. Unlike CSV, Parquet is a columnar, compressed, binary format that embeds schema metadata directly in the file - column names, data types, and statistics are all self-describing. This means no inference guesswork is required when loading data, and the strict typing aligns perfectly with Polars' philosophy of statically-known schemas.

We read parquet files using the polars.read_parquet method (or polars.scan_parquet for lazy loading).

The columnar layout delivers significant benefits for analytical workloads. Compression is highly effective because similar data types are stored together, resulting in files that are often 10-100x smaller than equivalent CSVs. More importantly, Polars can read only the columns your query actually needs without touching the rest of the file: a technique known as projection pushdown that dramatically reduces I/O.

So is a recommendation that if you are going to working with a large dataset stored in CSV format, it is often worthwhile to convert from CSV to Parquet because it will reduce the footprint of the data on the filesystem and improve the speed of the inner dev loop of exploring the data.

Intelligent Scan Optimisation

Where Polars really shines is in its use of Parquet's embedded statistics. Each Parquet file contains metadata about its row groups, including minimum and maximum values for each column. When you apply a filter in a lazy query, Polars examines these statistics and can skip entire row groups that cannot possibly contain matching rows - without reading any of the underlying data. Combined with predicate pushdown (applying filters at scan level rather than after materialisation), this means Polars often reads only a fraction of the file.

As Ritchie Vink explains: "if you do a filter, we look at the parquet statistics in the file and we will not first read the whole file and then apply the filter, we will apply the filters while we're reading it in." The result is that a well-optimised Parquet based workflow can be orders of magnitude faster than the equivalent CSV processing, with substantially lower memory consumption.

Loading multiple files in one operation

In practice, data lakes rarely consist of a single Parquet file. Upstream processes typically write data in partitions. Perhaps one file per day, per source system, or per logical partition. Rather than requiring you to enumerate each file individually, Polars supports glob patterns that match multiple files in a single operation.

We have simulated Hive-style partitioned data in the test data by creating a suite of parquet files using a partitioning strategy based on year. This results in one folder for each year and one (or potentially more) Parquet file within each folder.

Using the globbing pattern we can load all of the files in one operation using the following pattern where the * wildcard matches any characters within a single directory level (you can use ** to match across multiple directory levels).

metrics = pl.read_parquet(PARQUET_FOLDER / "year=*" / "*.parquet")

# Display 5 randomly sampled rows from the dataframe

metrics.select(["country_code", "country_name", "region", "year", "WB_WDI_SP_POP_TOTL"]).sample(5)

| country_code | country_name | region | year | WB_WDI_SP_POP_TOTL |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| str | str | str | i64 | f64 |

| CRI | Costa Rica | Latin America & Caribbean | 1974 | 2.039643e6 |

| NGA | Nigeria | Sub-Saharan Africa | 1985 | 8.4897973e7 |

| IDN | Indonesia | East Asia & Pacific | 2019 | 2.72489381e8 |

| CHN | China | East Asia & Pacific | 2018 | 1.4028e9 |

| ALB | Albania | Europe & Central Asia | 1975 | 2.404831e6 |

Loading multiple JSON files

Polars supports two primary JSON formats: newline-delimited JSON (NDJSON) and standard JSON arrays. NDJSON, where each line is a separate JSON object, is the more performant option for large datasets because it can be processed in a streaming fashion without loading the entire file into memory.

As with CSV, Polars infers the schema by sampling the data. The same principle applies: once the schema is established, it's enforced strictly throughout the query. For nested JSON structures, Polars maps these to its native Struct and List types, which are properly typed and benefit from Polars' vectorised execution.

That said, JSON is inherently less efficient than columnar formats for analytical workloads. It's row-oriented, text-based, and lacks the embedded statistics that enable predicate pushdown. If you're regularly processing JSON at scale, it's often worth converting to Parquet as a one-time transformation - you'll recoup the conversion cost quickly through faster subsequent reads.

In this example we are using the globbing functionality to load multiple JSON files simulating the type of raw data that is often generated from web APIs.

json_metrics = (

pl.read_ndjson(JSON_FOLDER / "*_data.json")

)

When we display the first 2 rows of the JSON data below, you can see that it has loaded two of the columns as custom datatypes. Polars has scanned the first N elements of JSON and determined that the country_info column contains a struct datatype with 6 elements. The indicators column contains a list[struct] an array of structs each with 4 elements.

This works really well if your JSON data is consistent in terms of structure and content. Leaving Polars to define the schema in this way for JSON data which can vary in structure beyond the first N rows can be problematic and will likely need manual definition of schema to load reliably.

# Display the first 2 rows of the dataframe.

json_metrics.head(2)

| country_code | country_info | indicators |

|---|---|---|

| str | struct[6] | list[struct[4]] |

| ALB | {"Albania","Europe & Central Asia","Upper middle income","Tirane","41.3317","19.8172"} | [{"WB_WDI_NY_GDP_PCAP_CD","GDP per capita (current US$)","Weighted average",[{2019,6069.439031}, {2004,2446.909499}, … {1986,693.873475}]}, {"WB_WDI_GC_DOD_TOTL_GD_ZS","Central government debt, total (% of GDP)","Weighted average",[{2019,74.808252}, {2017,74.523341}, … {1995,29.450991}]}, … {"WB_WDI_SP_DYN_LE00_IN","Life expectancy at birth, total (years)","Weighted average",[{2019,79.467}, {2004,75.951}, … {1973,67.107}]}] |

| ARG | {"Argentina","Latin America & Caribbean","Upper middle income","Buenos Aires","-34.6118","-58.4173"} | [{"WB_WDI_SP_DYN_LE00_IN","Life expectancy at birth, total (years)","Weighted average",[{2019,76.847}, {2004,74.871}, … {1970,65.647}]}, {"WB_WDI_SP_POP_TOTL","Population, total","Sum",[{2004,3.8815916e7}, {2013,4.2582455e7}, … {1970,2.3878327e7}]}, … {"WB_WDI_NY_GDP_MKTP_CD","GDP (current US$)","Gap-filled total",[{2019,4.4775e11}, {2004,1.6466e11}, … {1970,3.1584e10}]}] |

Loading from DuckDB

DuckDB and Polars are a powerful combination for data analysis. DuckDB is an in-process SQL OLAP database management system, which means it runs inside the same process as the application. This makes it incredibly fast for analytical queries.

The .pl() method provides a seamless way to convert the result of a DuckDB query into a Polars DataFrame, allowing you to move data efficiently between the two tools.

In the example below, we are doing a simple SELECT * FROM query to select all of the data from a single table. In the more detailed examples below, we show how to combine the power of DuckDB and Polars for more advanced analytics.

import duckdb

with duckdb.connect(f'{DUCKDB_PATH}', read_only=True) as duckdb_connection:

duck_data = duckdb_connection.sql('SELECT * FROM data').pl()

duck_data.glimpse()

Rows: 9715

Columns: 4

$ country_code <str> 'VNM', 'VNM', 'GBR', 'CAN', 'CHL', 'CHN', 'VNM', 'GBR', 'USA', 'VNM'

$ year <i64> 2011, 2018, 2016, 2010, 2010, 2010, 1999, 2009, 2009, 2009

$ indicator_code <str> 'WB_WDI_EG_USE_PCAP_KG_OE', 'WB_WDI_EG_USE_PCAP_KG_OE', 'WB_WDI_EG_USE_PCAP_KG_OE', 'WB_WDI_EG_USE_PCAP_KG_OE', 'WB_WDI_EG_USE_PCAP_KG_OE', 'WB_WDI_EG_USE_PCAP_KG_OE', 'WB_WDI_EG_USE_PCAP_KG_OE', 'WB_WDI_EG_USE_PCAP_KG_OE', 'WB_WDI_EG_USE_PCAP_KG_OE', 'WB_WDI_EG_USE_PCAP_KG_OE'

$ value <f64> 663.57444, 885.646842, 2696.97999, 7660.754521, 1795.68173, 1899.799961, 358.075426, 3144.002013, 7053.358467, 615.142147

Data Exploration

Once your data is loaded, Polars provides several methods to explore and understand it.

We have already shown a few examples above:

polars.DataFrame.head()- display the first N rows of the dataframe.polars.DataFrame.tail()- display the last N rows of the dataframe.polars.DataFrame.glimpse()- shows the values of the first few rows of a dataframe, but formats the output differently from head and tail. Here, each line of the output corresponds to a single column, making it easier to inspect wider dataframes.polars.DataFrame.sample()- samples n random rows from a DataFrame.polars.DataFrame.columns- provides a list of the columns in the dataframe.polars.DataFrame.describe()- generates summary statistics for the dataframe.

# Display the summary statistics for the dataframe.

countries.describe()

| statistic | country_code | iso2_code | country_name | region | region_id | income_level | capital_city | longitude | latitude |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| str | str | str | str | str | str | str | str | f64 | f64 |

| count | 296 | 296 | 296 | 296 | 296 | 296 | 211 | 211.0 | 211.0 |

| null_count | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 85 | 85.0 | 85.0 |

| mean | null | null | null | null | null | null | null | 19.139549 | 18.889009 |

| std | null | null | null | null | null | null | null | 70.391069 | 24.210877 |

| min | ABW | 1A | Afghanistan | Aggregates | EAS | Aggregates | Abu Dhabi | -175.216 | -41.2865 |

| 25% | null | null | null | null | null | null | null | -13.7 | 4.60987 |

| 50% | null | null | null | null | null | null | null | 19.2595 | 17.3 |

| 75% | null | null | null | null | null | null | null | 50.5354 | 40.0495 |

| max | ZWE | ZW | Zimbabwe | Sub-Saharan Africa | SSF | Upper middle income | Zagreb | 179.089567 | 64.1836 |

Polars Expressions

So far, we've covered the basics but where Polars starts to differentiate is through its composable, expressive API that adopts a functional programming approach - a good fit with data processing use cases.

The Polars team have worked hard to make the domain specific language (DSL) consistent and therefore intuitive to use.

The foundation of the language is the concept of "expressions": composable building blocks that each specialise in a specific data wrangling task such as:

- Filtering - filtering to a specific subset of data based on the values in specific columns.

- Aggregating, summarising - often applied when grouping up data based on categorical values.

- Selecting - trimming the dataframe down to specific columns that you want to analyse or display.

- Transforming - pivoting, unpivoting and other operations to unpack complex structures such as arrays and dictionaries.

- Joining - joining dataframes based on a relationship and specifying a join strategy (e.g. an "inner join" or "left outer join").

- Calculated columns - adding new columns which are derived from others in the dataframe.

- Cleaning - a diverse range of expressions are available to help clean up data, some examples include:

- Handling empty data - dropping nulls or using strategies such as forward filling to fill in data where it missing.

- Dropping duplicates.

- Adding unique IDs.

There are more specialised expressions which are generally organised under a specific namespace. For example polars.Expr.str is the namespace under which string based expressions are organised.

Polars expressions are functional abstractions over a Series, where a Series is an array of values with the same data type, e.g. List[polars.Int64]. They are often the contents of a specific column in your Polars dataframe, but they can also be created through other means (e.g. as a derived, intermediate result in a chain of expressions).

Each expression is elegantly simple: they take a Series as input and produce a Series as output. Because the input and output types are the same, expressions can be chained indefinitely, making them composable.

Ritchie Vink draws a compelling analogy: "just as Python's vocabulary is small (if, else, for, lists) yet can express anything through combination, Polars gives you a limited set of operations that combine to handle use cases the developers never anticipated. You learn a small API surface, then apply that knowledge everywhere."

With composable expressions, you stay within Polars' DSL. The engine can analyse, optimise, and parallelise your logic because it understands what you're doing.

In the examples below, we aim to show the flexibility and power of Polars expressions by applying them to the World Bank data based on common data wrangling scenarios.

Filtering and selecting

We've been asked to prepare an official list of countries to be used across our organisation as a "source of truth" across different types of analytics. This gives us an opportunity to show some of the most frequently used Polars functions: filter, select and sort.

The World Bank is deemed to be the source, but we spot that raw data for countries contains "aggregate" level results on top of data for individual countries. Therefore, we use polars.DataFrame.filter to filter the dataframe to only retain the country level data, using the ~ operator to negate the .is_in condition.

We then use polars.Dataframe.select to select the columns we want to publish from the range of columns available in the source dataframe.

Finally, we use the polars.DataFrame.sort expression so it is ordered by country name.

We chain these operations using a pattern commonly seen in functional programming style. This enables Polars to see the end to end intent of the operation and optimise it accordingly. It also provides code which is easy to read and maintain.

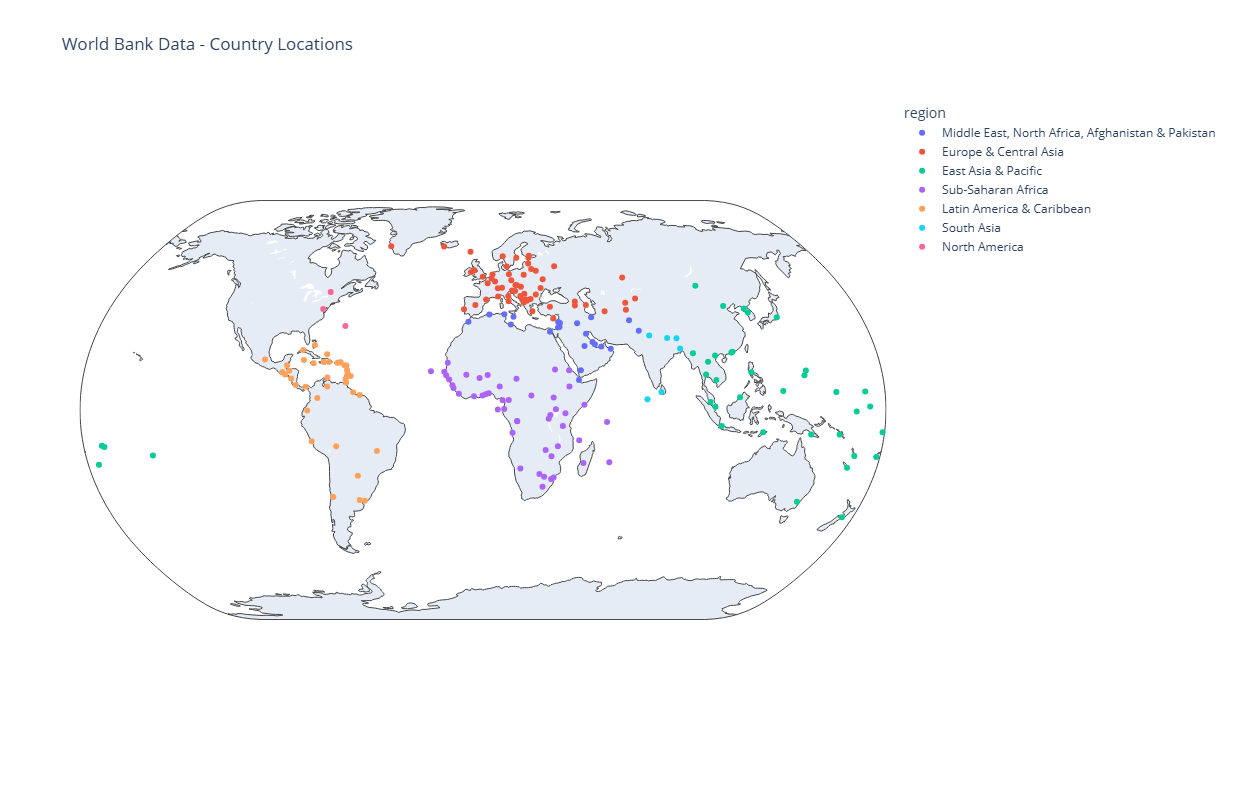

Polars works well with modern visualisation libraries such as plotly. So we can bring our final dataset to life by projecting it onto a map of the World.

# Inspection of the "region" column to see unique values shows an "Aggregates" category which we want to filter out.

countries["region"].unique()

| region |

|---|

| str |

| Sub-Saharan Africa |

| Latin America & Caribbean |

| South Asia |

| East Asia & Pacific |

| North America |

| Aggregates |

| Europe & Central Asia |

| Middle East, North Africa, Afg… |

# We don't want to publish all of the columns in the countries dataframe.

countries.columns

['country_code',

'iso2_code',

'country_name',

'region',

'region_id',

'income_level',

'capital_city',

'longitude',

'latitude']

countries = (

countries

.filter(~pl.col("region").is_in(["Aggregates"])) # Filter the data, using the ~ operator to negate the is_in condition so we exclude "Aggregates".

.select(["country_code", "iso2_code", "country_name", "region", "capital_city", "longitude", "latitude"]) # Select only relevant columns.

.sort(["country_name"]) # Sort by country name.

)

countries

| country_code | iso2_code | country_name | region | capital_city | longitude | latitude |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| str | str | str | str | str | f64 | f64 |

| AFG | AF | Afghanistan | Middle East, North Africa, Afg… | Kabul | 69.1761 | 34.5228 |

| ALB | AL | Albania | Europe & Central Asia | Tirane | 19.8172 | 41.3317 |

| DZA | DZ | Algeria | Middle East, North Africa, Afg… | Algiers | 3.05097 | 36.7397 |

| ASM | AS | American Samoa | East Asia & Pacific | Pago Pago | -170.691 | -14.2846 |

| AND | AD | Andorra | Europe & Central Asia | Andorra la Vella | 1.5218 | 42.5075 |

| … | … | … | … | … | … | … |

| VIR | VI | Virgin Islands (U.S.) | Latin America & Caribbean | Charlotte Amalie | -64.8963 | 18.3358 |

| PSE | PS | West Bank and Gaza | Middle East, North Africa, Afg… | null | null | null |

| YEM | YE | Yemen, Rep. | Middle East, North Africa, Afg… | Sana'a | 44.2075 | 15.352 |

| ZMB | ZM | Zambia | Sub-Saharan Africa | Lusaka | 28.2937 | -15.3982 |

| ZWE | ZW | Zimbabwe | Sub-Saharan Africa | Harare | 31.0672 | -17.8312 |

# Display the results on a geographical scatter plot.

fig = px.scatter_geo(

countries,

lat="latitude",

lon="longitude",

hover_name="country_name",

color="region", # Color points by region

projection="natural earth",

title="World Bank Data - Country Locations"

)

fig.show()

Calculated columns

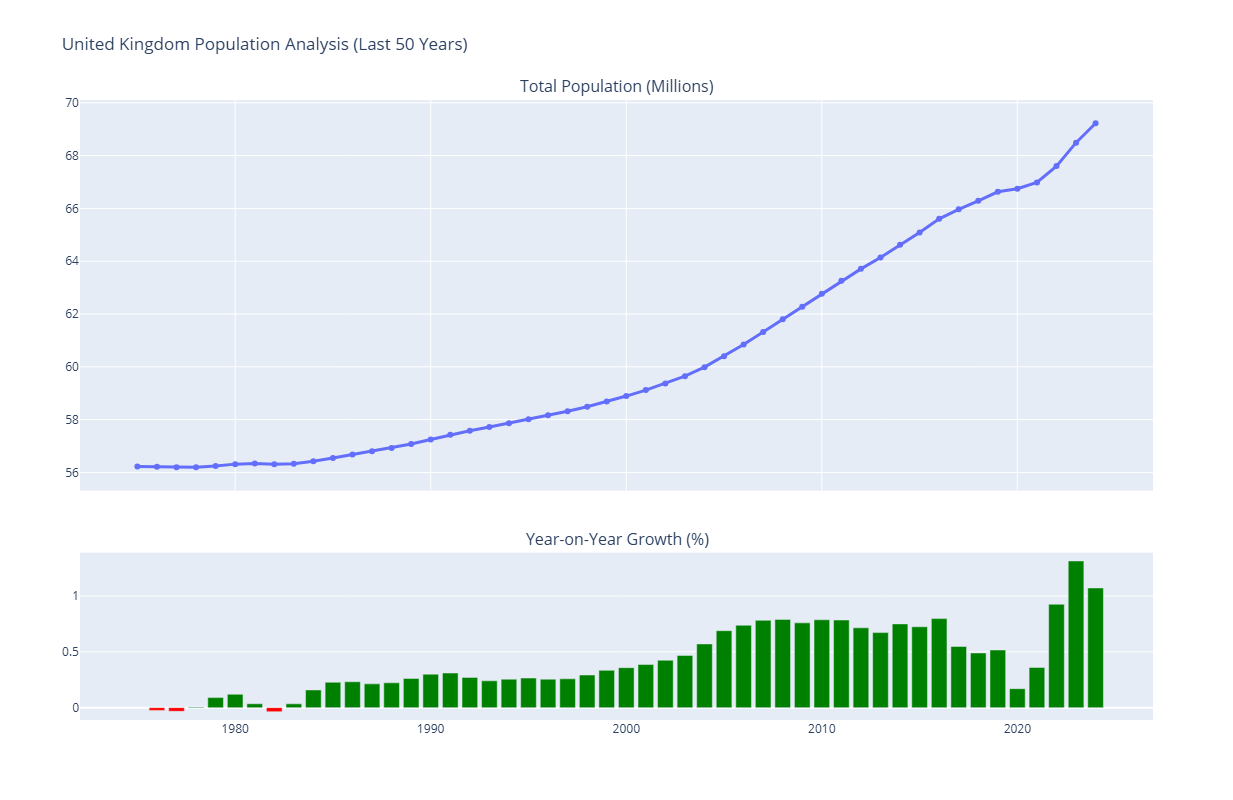

In the next example, we want to answer a simple question "How has the population (in millions) of the United Kingdom grown year on year over the last 50 years?".

In the dataset we loaded from Parquet, We have the population data in a column called WB_WDI_SP_POP_TOTL.

We need to filter this data in two dimensions:

- We only want data for the "United Kingdom"

- We only want data for the last 50 years.

We use polars.DataFrame.with_columns to add a new calculated column which converts the results into millions (making it easier for humans to reason with the data).

Next we need to sort the data in ascending order by year so we can then use the polars.Series.shift expression to enable the percentage change year on year to be calculated as a new column.

We then add a column using the polars.when function to create a final new column "color" which is set to a literal value of "green" when positive population growth, otherwise it is "red".

NUMBER_OF_YEARS = 50

uk_population = (

metrics

.filter((pl.col("country_name") == "United Kingdom") & (pl.col("year") > (int(metrics["year"].max()) - NUMBER_OF_YEARS))) # Filter in one step based on country name and year.

.with_columns((pl.col("WB_WDI_SP_POP_TOTL") / 1000000).alias("population_in_millions")) # Add a new column for population in millions.

.sort("year", descending=False)

.with_columns(

(((pl.col("population_in_millions") - pl.col("population_in_millions").shift(1))) / pl.col("population_in_millions").shift(1) * 100)

.alias("population_change_percentage") # Add new column for population change percentage.

)

.with_columns(

pl.when(pl.col("population_change_percentage") > 0)

.then(pl.lit("green"))

.otherwise(pl.lit("red"))

.alias("color") # Add new column for color based on population change.

)

.select(["year", "population_in_millions", "population_change_percentage", "color"])

)

uk_population

| year | population_in_millions | population_change_percentage | color |

|---|---|---|---|

| i64 | f64 | f64 | str |

| 1975 | 56.2258 | null | red |

| 1976 | 56.211968 | -0.024601 | red |

| 1977 | 56.193492 | -0.032868 | red |

| 1978 | 56.196504 | 0.00536 | green |

| 1979 | 56.246951 | 0.089769 | green |

| … | … | … | … |

| 2020 | 66.744 | 0.169591 | green |

| 2021 | 66.984 | 0.359583 | green |

| 2022 | 67.604 | 0.925594 | green |

| 2023 | 68.492 | 1.313532 | green |

| 2024 | 69.226 | 1.071658 | green |

# Create subplots with 2 rows and 1 column

fig = make_subplots(

rows=2, cols=1,

shared_xaxes=True,

vertical_spacing=0.1, # Space between charts

row_heights=[0.7, 0.3], # 70% height for main chart, 30% for bar chart

subplot_titles=("Total Population (Millions)", "Year-on-Year Growth (%)")

)

# Top Chart: Absolute Population (Line + Markers)

fig.add_trace(

go.Scatter(

x=uk_population["year"],

y=uk_population["population_in_millions"],

mode="lines+markers",

name="Population",

line=dict(width=3)

),

row=1, col=1

)

# Bottom Chart: Percentage Change (Bar)

fig.add_trace(

go.Bar(

x=uk_population["year"],

y=uk_population["population_change_percentage"],

marker_color=uk_population["color"], # Use the calculated red/green column

name="Change %"

),

row=2, col=1

)

# Update layout configuration

fig.update_layout(

title_text="United Kingdom Population Analysis (Last 50 Years)",

showlegend=False

)

fig.show()

Unpacking complex types

In the data loading examples above, we loaded a set of JSON files (one per country) that contained metrics for each country as an array of complex type.

Polars provides two useful functions to enable you unpack this type of data:

The

polars.DataFrame.unnestfunction is used to decompose struct columns, creating one new column for each of their fields. For example the columncountry_infocontains a dictionary-like structure with data such as{"country_name": "Argentina", "region": "Latin America & Caribbean ", "income_level": "Upper middle income", "capital_city": "Buenos Aires", "longitude": "-34.6118", "latitude": "-58.4173"}, when we call theunnestoperation on this column, it creates 4 new columns (country_name,region,income_level,capital_city,longitudeandlatitude) and populates these columns with the values in those respective elements of the dictionary-like structure.The

polars.DataFrame.explodemethod is used to unpack columns which contain an array (list) object. Exploding the data by creating a row for each unique value in the array.

The net result is we can flatten out the nested data into a tabular form, making it ready for downstream analytics.

json_metrics = (

json_metrics

.explode("indicators") # Turn list of indicators into individual row for each indicator

.unnest("indicators") # Unpack the indicators object into individual components

.explode("data_points") # Explode the data_points (a list of {"year: XXXX, "value": XXXX}) into individual rows

.unnest("data_points") # Unpack the datapoints into separate columns for `year` and `value`

.unnest("country_info") # Unpack the country_info object into individual columns

)

json_metrics

| country_code | country_name | region | income_level | capital_city | latitude | longitude | indicator_code | indicator_name | aggregation_method | year | value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| str | str | str | str | str | str | str | str | str | str | i64 | f64 |

| ALB | Albania | Europe & Central Asia | Upper middle income | Tirane | 41.3317 | 19.8172 | WB_WDI_NY_GDP_PCAP_CD | GDP per capita (current US$) | Weighted average | 2019 | 6069.439031 |

| ALB | Albania | Europe & Central Asia | Upper middle income | Tirane | 41.3317 | 19.8172 | WB_WDI_NY_GDP_PCAP_CD | GDP per capita (current US$) | Weighted average | 2004 | 2446.909499 |

| ALB | Albania | Europe & Central Asia | Upper middle income | Tirane | 41.3317 | 19.8172 | WB_WDI_NY_GDP_PCAP_CD | GDP per capita (current US$) | Weighted average | 2013 | 4542.929036 |

| ALB | Albania | Europe & Central Asia | Upper middle income | Tirane | 41.3317 | 19.8172 | WB_WDI_NY_GDP_PCAP_CD | GDP per capita (current US$) | Weighted average | 2000 | 1160.420471 |

| ALB | Albania | Europe & Central Asia | Upper middle income | Tirane | 41.3317 | 19.8172 | WB_WDI_NY_GDP_PCAP_CD | GDP per capita (current US$) | Weighted average | 2008 | 4498.504868 |

| … | … | … | … | … | … | … | … | … | … | … | … |

| ZAF | South Africa | Sub-Saharan Africa | Upper middle income | Pretoria | -25.746 | 28.1871 | WB_WDI_SL_UEM_TOTL_ZS | Unemployment, total (% of tota… | Weighted average | 2000 | 22.714 |

| ZAF | South Africa | Sub-Saharan Africa | Upper middle income | Pretoria | -25.746 | 28.1871 | WB_WDI_SL_UEM_TOTL_ZS | Unemployment, total (% of tota… | Weighted average | 1999 | 22.791 |

| ZAF | South Africa | Sub-Saharan Africa | Upper middle income | Pretoria | -25.746 | 28.1871 | WB_WDI_SL_UEM_TOTL_ZS | Unemployment, total (% of tota… | Weighted average | 1995 | 22.647 |

| ZAF | South Africa | Sub-Saharan Africa | Upper middle income | Pretoria | -25.746 | 28.1871 | WB_WDI_SL_UEM_TOTL_ZS | Unemployment, total (% of tota… | Weighted average | 1991 | 23.002 |

| ZAF | South Africa | Sub-Saharan Africa | Upper middle income | Pretoria | -25.746 | 28.1871 | WB_WDI_SL_UEM_TOTL_ZS | Unemployment, total (% of tota… | Weighted average | 1996 | 22.48 |

json_metrics["indicator_code"].unique()

| indicator_code |

|---|

| str |

| WB_WDI_SP_POP_TOTL |

| WB_WDI_GC_DOD_TOTL_GD_ZS |

| WB_WDI_EG_USE_PCAP_KG_OE |

| WB_WDI_SE_ADT_LITR_ZS |

| WB_WDI_NY_GDP_MKTP_CD |

| WB_WDI_NY_GDP_PCAP_CD |

| WB_WDI_SL_UEM_TOTL_ZS |

| WB_WDI_SP_DYN_LE00_IN |

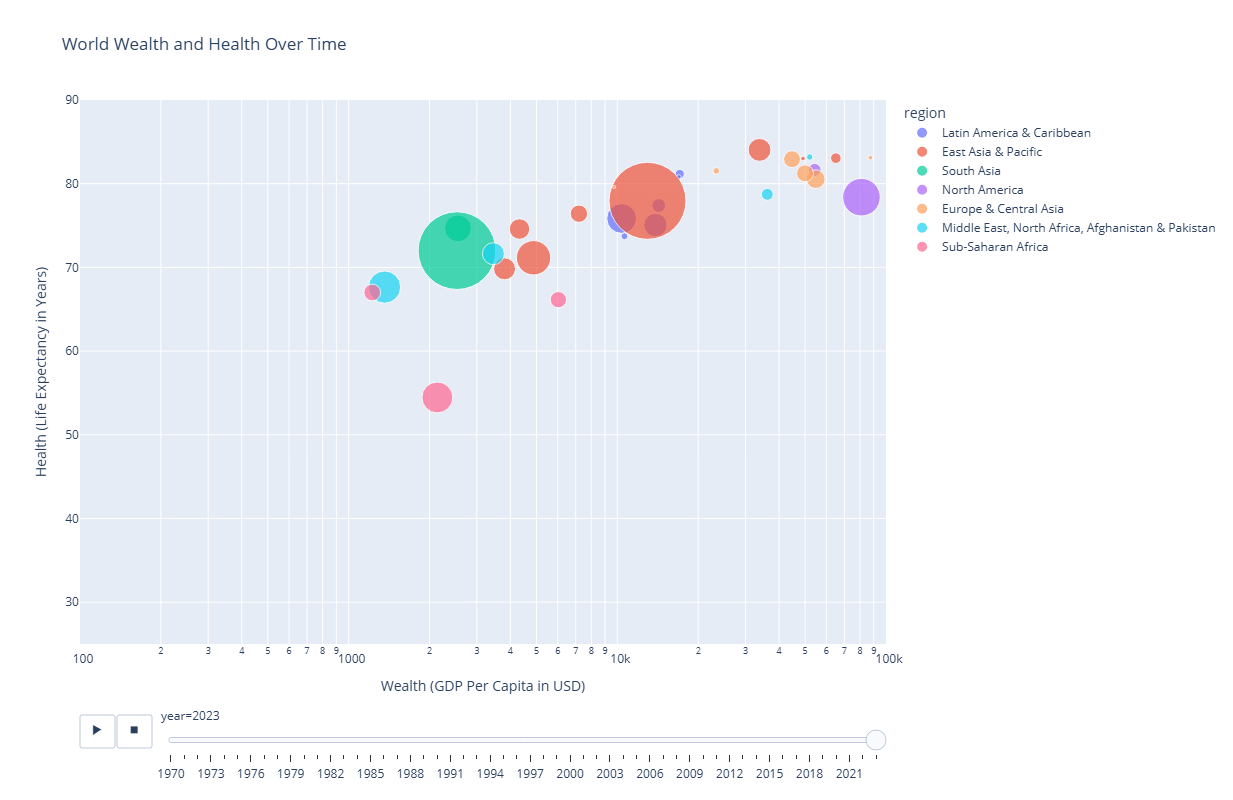

Complex transformation, leveraging DuckDB and Polars

When you pair DuckDB with Polars, you get the best of both worlds:

- High-Performance SQL: Use DuckDB's fast SQL engine to perform initial filtering, aggregation, and data manipulation at the database level.

- Expressive DataFrame API: Load the results directly into a Polars DataFrame to leverage its powerful and expressive API for more complex transformations and analysis.

In this example, we are first going to use a DuckDB prepare the data through a more complex query which joins two tables and filters the data through a WHERE clause.

with duckdb.connect(f'{DUCKDB_PATH}', read_only=True) as duckdb_connection:

duckdb_query_results = duckdb_connection.sql(

"""

SELECT d.country_code, c.country_name, c.region, d.year, d.indicator_code, d.value

FROM data d

JOIN countries c ON d.country_code = c.country_code

WHERE d.indicator_code IN ('WB_WDI_SP_POP_TOTL', 'WB_WDI_SP_DYN_LE00_IN', 'WB_WDI_NY_GDP_PCAP_CD')

"""

).pl()

duckdb_query_results.head(3)

| country_code | country_name | region | year | indicator_code | value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| str | str | str | i64 | str | f64 |

| VNM | Viet Nam | East Asia & Pacific | 2011 | WB_WDI_NY_GDP_PCAP_CD | 1950.925042 |

| VNM | Viet Nam | East Asia & Pacific | 2018 | WB_WDI_NY_GDP_PCAP_CD | 3222.310031 |

| GBR | United Kingdom | Europe & Central Asia | 2016 | WB_WDI_NY_GDP_PCAP_CD | 41257.908555 |

Next we are going to use a polars.DataFrame.pivot operation to transform the shape of the dataframe and get the data ready to plot on a chart.

world_wealth_and_health = (

duckdb_query_results

.pivot(

on=["indicator_code"],

index=["country_code", "country_name", "region", "year"],

values="value"

)

.rename(

{

"WB_WDI_NY_GDP_PCAP_CD": "gdp_usd_per_capita",

"WB_WDI_SP_DYN_LE00_IN": "life_expectancy",

"WB_WDI_SP_POP_TOTL": "population"

}

)

.drop_nulls(subset=["gdp_usd_per_capita", "life_expectancy", "population"]) # Drop rows with nulls in any of the key metrics

.with_columns(

[

(pl.col("population") / 1000000).round(2).alias("population_in_millions"),

]

)

.sort(["year", "country_code"])

)

world_wealth_and_health.head(3)

| country_code | country_name | region | year | gdp_usd_per_capita | life_expectancy | population | population_in_millions |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| str | str | str | i64 | f64 | f64 | f64 | f64 |

| ARG | Argentina | Latin America & Caribbean | 1970 | 1322.714542 | 65.647 | 2.3878327e7 | 23.88 |

| AUS | Australia | East Asia & Pacific | 1970 | 3309.763063 | 71.018537 | 1.2507e7 | 12.51 |

| BGD | Bangladesh | South Asia | 1970 | 130.218161 | 42.667 | 6.9058894e7 | 69.06 |

Finally we chart the results to show the snail trail of each country over time on a two dimensional scatter chart.

fig = px.scatter(

world_wealth_and_health,

x="gdp_usd_per_capita",

y="life_expectancy",

animation_frame="year",

animation_group="country_name",

size="population_in_millions",

color="region",

hover_name="country_name",

log_x=True,

size_max=55,

range_x=[100, 100000],

range_y=[25, 90],

title="World Wealth and Health Over Time",

labels={

"gdp_usd_per_capita": "Wealth (GDP Per Capita in USD)",

"life_expectancy": "Health (Life Expectancy in Years)"

}

)

fig.show()

Lazy loading

# Read CSV using lazy frame

data = pl.scan_parquet(PARQUET_FOLDER, hive_partitioning=True)

# The `scan_parquet returns a lazy frame not the data, But it does inspect the files.

data

naive plan: (run LazyFrame.explain(optimized=True) to see the optimized plan)

# We can inspect the schema without loading data

data.collect_schema()

Schema([('country_code', String),

('year', Int64),

('WB_WDI_EG_USE_PCAP_KG_OE', Float64),

('WB_WDI_GC_DOD_TOTL_GD_ZS', Float64),

('WB_WDI_NY_GDP_MKTP_CD', Float64),

('WB_WDI_NY_GDP_PCAP_CD', Float64),

('WB_WDI_SE_ADT_LITR_ZS', Float64),

('WB_WDI_SL_UEM_TOTL_ZS', Float64),

('WB_WDI_SP_DYN_LE00_IN', Float64),

('WB_WDI_SP_POP_TOTL', Float64),

('country_name', String),

('region', String)])

# Start to build up some operations on the lazy frame

data = (

data

.rename({"WB_WDI_SP_POP_TOTL": "population"}) # Rename the value column to population

)

# We want use 1980 as the base year for our analysis

data = data.filter(pl.col("year") >= 1980)

# Normalise each country's population so it has a maximum of 1 for all years since 1980

data = (

data

.with_columns(

pl.col("population")

.max()

.over("country_code")

.alias("max_population") # Get max population per country

)

.with_columns(

(pl.col("population") / pl.col("max_population")).alias("normalized_population") # Normalized population

)

.drop("max_population") # Drop the intermediate column

)

# Select the final set of columns we want to publish

data = data.select([

"country_code",

"country_name",

"region",

"year",

"population",

"normalized_population",

])

# We only want to see data for a selection of countries and from 1980 onwards

data = (

data

.filter(pl.col("country_code").is_in(["CHN", "UK", "ALB", "JPN", "NZL", "CAN"])) # Filter for specific countries and years

)

At this stage we haven't executed the steps we have built up above. We compare the query plans generated by explain(optimized=True) versus explain(optimized=False) - each shows nested sets of steps in reverse order. A quick scan shows the following key differences:

The un-optimized plan follows the steps in the order we defined them above.

# The un-optimized plan shows all the steps we have built up above.

print(data.explain(optimized=False))

FILTER col("country_code").is_in([["CHN", "UK", … "CAN"]])

FROM

SELECT [col("country_code"), col("country_name"), col("region"), col("year"), col("population"), col("normalized_population")]

SELECT [col("country_code"), col("year"), col("WB_WDI_EG_USE_PCAP_KG_OE"), col("WB_WDI_GC_DOD_TOTL_GD_ZS"), col("WB_WDI_NY_GDP_MKTP_CD"), col("WB_WDI_NY_GDP_PCAP_CD"), col("WB_WDI_SE_ADT_LITR_ZS"), col("WB_WDI_SL_UEM_TOTL_ZS"), col("WB_WDI_SP_DYN_LE00_IN"), col("population"), col("country_name"), col("region"), col("normalized_population")]

WITH_COLUMNS:

[[(col("population")) / (col("max_population"))].alias("normalized_population")]

WITH_COLUMNS:

[col("population").max().over([col("country_code")]).alias("max_population")]

FILTER [(col("year")) >= (1980)]

FROM

SELECT [col("country_code"), col("year"), col("WB_WDI_EG_USE_PCAP_KG_OE"), col("WB_WDI_GC_DOD_TOTL_GD_ZS"), col("WB_WDI_NY_GDP_MKTP_CD"), col("WB_WDI_NY_GDP_PCAP_CD"), col("WB_WDI_SE_ADT_LITR_ZS"), col("WB_WDI_SL_UEM_TOTL_ZS"), col("WB_WDI_SP_DYN_LE00_IN"), col("WB_WDI_SP_POP_TOTL").alias("population"), col("country_name"), col("region")]

Parquet SCAN [../data/world_bank/parquet/year=1970/af92515fa293459c9aa99c6433ee2cda.parquet, ... 54 other sources]

PROJECT 11/12 COLUMNS

ESTIMATED ROWS: 1760

The optimized plan shows less steps and a different ordering of operations because Polars has applied multiple levels of optimization:

- Predicate Pushdown: Look for

SELECTIONin the scan node. Polars has pushed the filter logic down to the data access layer. Instead of reading all rows into memory and then filtering them, it applies the filter during the scan, discarding non-matching rows immediately. - Projection Pushdown: In the Optimized plan, look for

PROJECT */* COLUMNS. Polars analysed your query and determined exactly which columns are needed. It will strictly only read those specific columns from disk, ignoring the rest to save memory and I/O. - Intelligent Scan Optimisation: This combines Partition Pruning and Parquet Statistics.

- Partition Pruning: Because we used

hive_partitioning=Trueand filtered onyear, Polars checks the folder names first. It completely skips opening files for years 1960-1979, only reading files that match the filter. - Row Group Statistics: Unique to Parquet (vs CSV/JSON), these files contain metadata with min/max values for chunks of data ("Row Groups"). If we filtered on a data column, Polars would check these stats and skip reading entire chunks of the file if they couldn't possibly contain matching data.

- Partition Pruning: Because we used

# The optimized plan shows how Polars will execute the query efficiently.

print(data.explain())

simple π 6/6 ["country_code", "country_name", ... 4 other columns]

WITH_COLUMNS:

[[(col("population")) / (col("max_population"))].alias("normalized_population")]

WITH_COLUMNS:

[col("population").max().over([col("country_code")]).alias("max_population")]

SELECT [col("country_code"), col("year"), col("WB_WDI_SP_POP_TOTL").alias("population"), col("country_name"), col("region")]

Parquet SCAN [../data/world_bank/parquet/year=1980/77399e87ba29443cb65b5a3fff361036.parquet, ... 44 other sources]

PROJECT 5/12 COLUMNS

SELECTION: [([(col("year")) >= (1980)]) & (col("country_code").is_in([["CHN", "UK", … "CAN"]]))]

ESTIMATED ROWS: 1440

Now we can actually run the end to end logic to ingest the data and perform the optimised chain of operations on it by calling the polars.lazyframe.collect method.

# Get the data by executing `.collect()` on the lazy frame

data.collect()

| country_code | country_name | region | year | population | normalized_population |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| str | str | str | i64 | f64 | f64 |

| NZL | New Zealand | East Asia & Pacific | 1980 | 3.1129e6 | 0.588728 |

| JPN | Japan | East Asia & Pacific | 1980 | 1.16807e8 | 0.912056 |

| CAN | Canada | North America | 1980 | 2.4515667e7 | 0.593764 |

| CHN | China | East Asia & Pacific | 1980 | 9.81235e8 | 0.694749 |

| ALB | Albania | Europe & Central Asia | 1980 | 2.671997e6 | 0.813012 |

| … | … | … | … | … | … |

| CAN | Canada | North America | 2024 | 4.1288599e7 | 1.0 |

| JPN | Japan | East Asia & Pacific | 2024 | 1.23975371e8 | 0.968028 |

| NZL | New Zealand | East Asia & Pacific | 2024 | 5.2875e6 | 1.0 |

| ALB | Albania | Europe & Central Asia | 2024 | 2.377128e6 | 0.723292 |

| CHN | China | East Asia & Pacific | 2024 | 1.4090e9 | 0.997603 |

This may seem like a lot of additional steps for this relatively small amount of demo data we are using. But as you scale up to many Gigabytes with thousands of Parquet files in a lakehouse architecture, this approach will generate significant performance gains.

Final step is to bring our analysis to life with a chart.

# Plot the result one line per country showing normalized population over time

line_chart = px.line(

data.collect(),

x="year",

y="normalized_population",

color="country_name",

title="Normalized Population Growth Since 1980",

markers=True

)

line_chart.show()

Streaming Execution

In the example above, we used .collect() to materialize the final result into memory. For the amount of data we are working with here, this is perfectly fine.

However, one of Polars' most powerful features is its Streaming Engine.

If your dataset is larger than your machine's available RAM, a standard .collect() would result in an "Out of Memory" (OOM) error. By simply passing the streaming=True argument, you instruct Polars to process the data in batches.

It effectively pipelines the data processing, reading a chunk of data, processing it, and keeping only the results needed (e.g. the aggregated counts or the filtered rows) before moving on to the next chunk.

This allows you to process 100GB+ datasets on a standard laptop!

Conclusion

Hopefully, these worked examples have given you a flavour of Polars and provided some useful tips for applying it to your own use cases.

Throughout this notebook, we've demonstrated the key pillars that make Polars a game-changer for data engineering in Python, enabling you to express complex data transformations in a clear, concise, and performant way:

- Seamless Data Ingestion: First-class support for common formats like Parquet, CSV, and JSON makes loading data trivial.

- Expressive, Composable API: The functional API design allows you to build complex logic that remains readable and maintainable.

- Performance by Design: Under the hood, the Rust-based engine leverages vectorized execution and parallelization to handle heavy data wrangling tasks effortlessly.

- Lazy Evaluation: By switching to

LazyFrames, you hand control to the Query Optimizer. This unlocks techniques like Predicate Pushdown and Projection Pushdown, which can deliver huge performance gains just by letting Polars decide how to execute your query. - Streaming Execution: The

streaming=Trueoption breaks the memory barrier, allowing you to process datasets larger than your machine's RAM without needing a cluster.

As you become more familiar with Polars' capabilities, you'll find that it allows you to handle increasingly complex data tasks with elegance and efficiency. The expression-based API, lazy evaluation, and thoughtful design make it a powerful tool for modern data analysis.

This is Part 3 of our Adventures in Polars series:

- Part 1: Why Polars Matters - The Decision Makers Guide for Polars.

- Part 2: What Makes Polars So Scalable and Fast? - The technical deep-dive: lazy evaluation, query optimisation, parallelism, and the Rust foundation.

- Part 4: Polars Workloads on Microsoft Fabric - Running Polars on Fabric with OneLake integration.

What data analysis tasks have you tackled with Polars? Have you found particularly elegant solutions to common problems? Share your experiences in the comments below!