How .NET 7.0 boosted AIS.NET performance by 19%

At endjin, we maintain Ais.Net, an open source high-performance library for parsing AIS message (the radio messages that ships broadcast to report their location, speed, etc.). Last year when .NET 6.0 came out, we re-ran our benchmarks, and found that .NET 6.0 had given us a 20% performance boost.

We've just repeated this experiment with .NET 7.0, and the free lunch has continued! Without making any changes whatsoever to our code, our benchmarks improved by roughly 19% simply by running the code on .NET 7.0 instead of .NET 6.0. We've not had to release a new version—the existing version published on NuGet (which targets netstandard2.0 and netstandard2.1) sees these performance gains the moment you use it in a .NET 7.0 application.

Our memory usage seems to have remained consistent. Our amortized allocation cost per record continues to be 0 bytes. The total memory usage including startup costs has remained about the same at a handful of kilobytes, depending on exactly which features you use.

Benchmark results

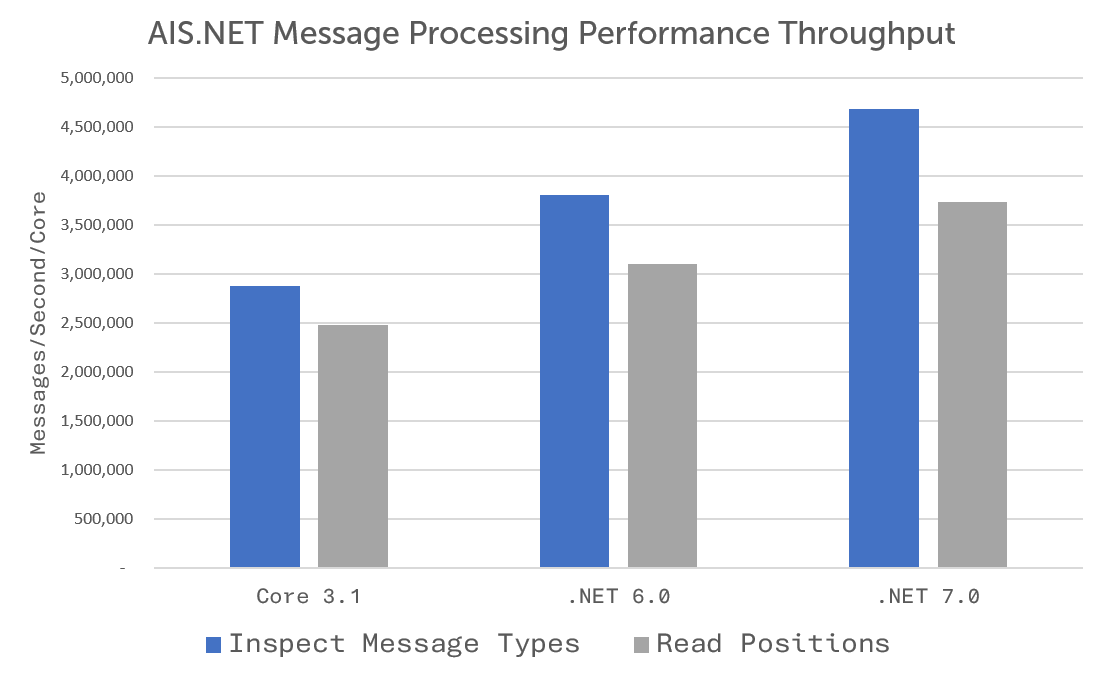

We have two benchmarks. One measures the maximum possible rate of processing messages, while doing as little work as possible for each message. This is not entirely realistic, but it's useful because it establishes the upper bound on how fast an application can process AIS messages on a single thread. The second benchmark uses a slightly more realistic workload, inspecting several properties from each message. Each benchmark runs against a file containing one million AIS records.

When I tested on .NET 6.0 in January 2022, I saw the results shown in this next table when running the benchmarks on my desktop. These figures correspond to an upper bound of 3.82 million messages per second, and a processing rate of 3.12 million messages a second for the slightly more realistic example. (My desktop is about 5 years old, and it has an Intel Core i9-9900K CPU.)

| Method | Mean | Error | StdDev | Allocated |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| InspectMessageTypesFromNorwayFile1M | 262.9 ms | 3.21 ms | 2.84 ms | 5 KB |

| ReadPositionsFromNorwayFile1M | 322.8 ms | 4.50 ms | 3.99 ms | 7 KB |

I repeated the results just now, a year and a half later, running on .NET 6.0.20, partly to verify that I've not somehow changed my machine in a way that affects the performance, and also to see whether updates to .NET 6.0 have changed the performance since I first ran the tests. Nothing seems to have changed—running the same benchmarks today produces results very similar to the ones shown above. I see slight variations between runs, including, surprisingly, the memory usage—each test varies between 5KB and 7KB from run to run. But there doesn't seem to have been any significant drift.

Here are the results for the same benchmarks running on .NET 7.0:

| Method | Mean | Error | StdDev | Allocated |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| InspectMessageTypesFromNorwayFile1M | 213.8 ms | 4.25 ms | 4.55 ms | 4 KB |

| ReadPositionsFromNorwayFile1M | 267.9 ms | 3.74 ms | 3.31 ms | 5 KB |

This shows that on .NET 7.0, our upper bound moves up to 4.78 million messages per second, while the processing rate for the more realistic example goes up to 3.72 million messages per second. Those are improvements of 25% and 19% respectively. (The first figure sounds more impressive, obviously, but I put the 19% figure in the blog title because that benchmark better represents what a real application might do.)

The bottom line is that just as moving your application onto .NET 6.0 last year may well have given you an instant performance boost with no real effort on your part, you may enjoy a similar boost upgrading to .NET 7.0.

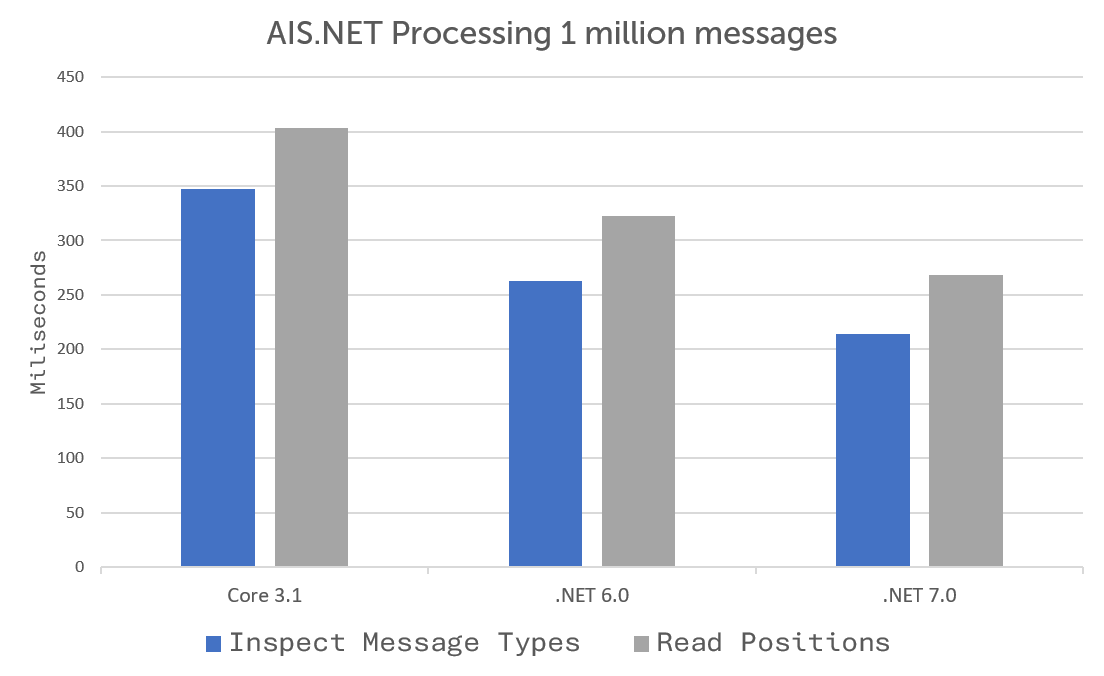

Now that we have 3 sets of measurements (.NET Core 3.1, .NET 6.0 and .NET 7.0) we can visualize the free performance gains we received. First we'll look at the time taken to process 1 million AIS messages:

And next, the throughput in AIS messages per second:

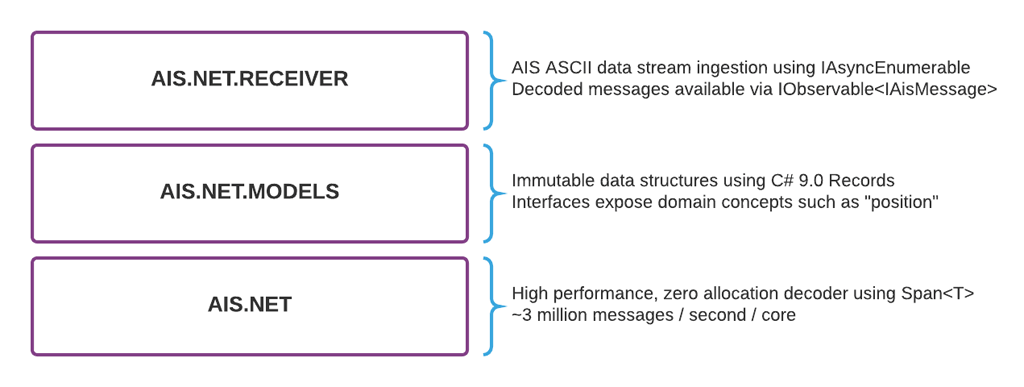

You can learn more about our Ais.Net library at the GitHub repo, http://github.com/ais-dotnet/Ais.Net/ and in the same ais-dotnet GitHub organisation you'll also find some other layers, as illustrated in this diagram:

Note that Ais.Net.Models is currently inside the Ais.Net.Receiver repository. If you would like to experiment with this library, you will find some polyglot notebooks illustrating its use at https://github.com/ais-dotnet/Ais.Net.Notebooks