T4 templates on modern .NET

T4 is a popular .NET-based templating language. Originally, it could use only .NET Framework, but in 2023, Microsoft added a version of the template tool that could use .NET 6.0. At some later point they added support for .NET 8.0. (As I write this in February 2026, there was not yet support for .NET 10.0.)

However, this modern .NET support is minimal, and is not used by default. The Visual Studio integration continues to use the old .NET Framework implementation. To use the new modern .NET support, you have to run the command line tool manually, or adapt your project files to invoke the tool for you.

The Rx.NET and Reaqtor codebases make extensive use of T4. Up until now we've relied on the built-in Visual Studio support, but the inability to use modern .NET features is starting to become a problem. This post explains what it takes to move projects that use the old .NET Framework T4 support in Visual Studio over to using T4 with modern .NET.

A quick introduction to T4

The documentation seems coy about what the name T4 means, but some say it stands for Text Template Transformation Toolkit. If you've not used T4 before, it's a bit like a Razor page–it can contain a mixture of plain text and C# code. For example:

<#@ template language="C#" #>

This is some plain text that will be emitted verbatim.

<#

// This code is executed, so it won't appear in the output, but it

// changes how the output that follows is produced.

for (int i = 0; i < 5; ++i)

{

#>

This is also emitted. It's in a loop, so we get many copies.

<#

// This is another code block.

}

#>

If I put that in a file called SimpleTemplate.tt and then run this command:

TextTransformCore SimpleTemplate.tt

it produces a file called SimpleTemplate.txt with this content:

This is some plain text that will be emitted verbatim.

This is also emitted. It's in a loop, so we get many copies.

This is also emitted. It's in a loop, so we get many copies.

This is also emitted. It's in a loop, so we get many copies.

This is also emitted. It's in a loop, so we get many copies.

This is also emitted. It's in a loop, so we get many copies.

I've made my template emit plain text in this example to clarify the fact that T4 is fundamentally text-oriented. You could use it to generate C#, F#, VB.NET, markdown, HTML, Cucumber specs, or, as in this case, just plain text containing natural language.

In Rx.NET and Reaqtor we use T4 to generate repetitive code. For example, the Min and Max operators have multiple versions of what are essentially the same code, just for different numeric types. (Since .NET 7, there has been a better way to solve this particular problem: it introduced of new ways of defining interfaces, and the associated generic math feature. However, we still target .NET Framework in Rx.NET, so we can't use that.) We also often use templates driven by reflection to generate code whose structure is determined by other code.

Aren't we supposed to be using source generators now?

In theory the introduction of source generators renders T4 unnecessary for the ways we use it in Rx.NET and Reaqtor. Now there is direct support in the .NET SDK for generating code at build time.

However, having written a couple of source generators I find them to be a major step up in complexity from T4.

They enable developers to create really useful tools. For example, our Corvus.JsonSchema libraries offer Corvus.Json.SourceGenerator, which is now my go-to solution when I want to deal with JSON in C#. But while source generators can be great to use, they are a bit of a nightmare to write. So I think there is still a place for T4.

Tooling changes

To understand how to migrate an existing project to using .NET in T4, it's important to understand the differences in tooling support for T4 on .NET FX and T4 on .NET.

Visual Studio's existing support for .NET FX

Visual Studio has offered support for T4 for many years. You enabled it by adding this to your project file:

<ItemGroup>

<Service Include="{508349b6-6b84-4df5-91f0-309beebad82d}" />

</ItemGroup>

You could then tell Visual Studio that certain source files were T4 templates, and normally you would also tell it about the association between the T4 template and its generated output, e.g.:

<ItemGroup>

<None

Update="Example.tt"

Generator="TextTemplatingFileGenerator"

LastGenOutput="Example.cs"

/>

<Compile

Update="Example.cs"

DesignTime="True"

AutoGen="True"

DependentUpon="Example.tt"

/>

</ItemGroup>

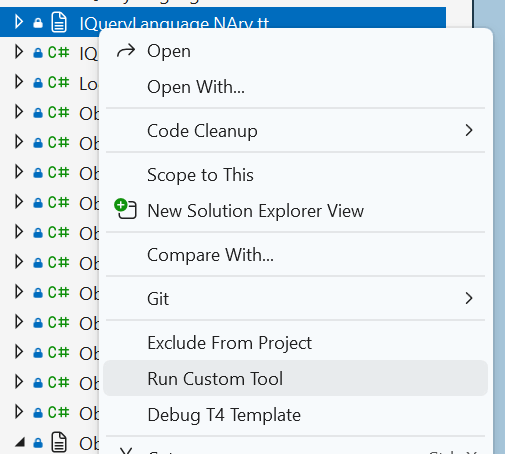

The <None> element here sets the Generator attribute to TextTemplatingFileGenerator, and this makes Visual Studio offer a couple of additional options on the file's context menu in Solution Explorer:

Selecting Run Custom Tool causes the T4 template to execute, generating its output. The Debug T4 Template runs it in the debugger so you can step through the template code.

T4 on .NET

The more recently added support for T4 on .NET provides one thing: the TextTransformCore command line tool. There is no Visual Studio integration. There is no supported way to tell Visual Studio to execute a template using .NET–VS (today) only offers the old .NET Framework-based T4 execution that has had for years.

So the new .NET support is all very bare bones. We get almost nothing compared to the support available when running a T4 template on .NET Framework. The old context menu items are still available, it's just that they can only invoke the old .NET Framework T4 tooling.

Changes required when using migrating T4 from .NET Framework to .NET

Note that if your are using assembly directives in your template you might need to change them because some .NET runtime library types are in different assemblies. For example, if a template written to run on .NET FX includes this line:

<#@ assembly name="System.Core" #>

you will probably need to change it to this to get it working on .NET:

<#@ assembly name="System.Linq" #>

You might also find that you are getting errors such as these:

Compiling transformation: CS1069: The type name 'Stack<>' could not be found in the namespace 'System.Collections.Generic'. This type has been forwarded to assembly 'System.Collections, Version=0.0.0.0, Culture=neutral, PublicKeyToken=b03f5f7f11d50a3a' Consider adding a reference to that assembly.

You may need to add this:

<#@ assembly name="System.Collections" #>

A more subtle problem is that the T4 tooling does not understand the distinction between reference assemblies and runtime assemblies. It always uses the latter, which can cause some surprises. For example, you might get an error of this form when trying to use the types in System.Xml.Linq:

error CS1069: Compiling transformation: CS1069: The type name 'XElement' could not be found in the namespace 'System.Xml.Linq'. This type has been forwarded to assembly 'System.Private.Xml.Linq, Version=8.0.0.0, Culture=neutral, PublicKeyToken=cc7b13ffcd2ddd51' Consider adding a reference to that assembly.

You can resolve this by adding another assembly directive:

<#@ assembly name="System.Private.Xml.Linq" #>

but this is somewhat unsatisfactory: the fact that .NET 8.0 happens to put this type in this assembly is an implementation detail that could easily change from one version of .NET to the next. But for now this seems to be the only way to work around this. I've submitted a bug report at https://developercommunity.visualstudio.com/t/TextTransformCore-uses-runtime-not-ref/11013312? if you're having the same problem and want to add your support for this being fixed.

Better project support for T4 on .NET

Although there is no built in tooling, it's actually relatively straightforward to make an existing project use the newer tooling, once you know how. We can do this with some modifications to project files. The basic process is:

- Define an

ItemGroupfor all your T4 templates - Automatically set the

DependentUponitem metadata on the generated code (to ensure generated files go underneath their T4 files) - Define a custom

Targetthat runs the T4 templates if the templates are newer than the generated outputs

Defining an item group for templates

I put this in a Directory.build.props file at the root of my solution, so that .tt files anywhere in any project in my solution are added to the item group:

<ItemGroup>

<TextTemplates Include="**\*.tt">

<GeneratedOutput>%(Filename).cs</GeneratedOutput>

<GeneratedOutputRelativePath>%(RelativeDir)%(GeneratedOutput)</GeneratedOutputRelativePath>

</TextTemplates>

</ItemGroup>

The Include="**\*.tt" is a glob that adds all files with a .tt extension anywhere in any project to the TextTemplates item group.

We then set two item metadata values:

GeneratedOutput: the filename of the output that the template will generateGeneratedOutputRelativePath: the path of the template output relative to the project folder

In fact, in the Reaqtor codebase, we do something slightly more complex:

<ItemGroup>

<TextTemplates Include="**\*.tt">

<GeneratedOutput Condition="Exists('%(RootDir)%(Directory)%(Filename).generated.cs')">%(Filename).generated.cs</GeneratedOutput>

<GeneratedOutput Condition="%(GeneratedOutput) == ''">%(Filename).cs</GeneratedOutput>

<GeneratedOutputRelativePath>%(RelativeDir)%(GeneratedOutput)</GeneratedOutputRelativePath>

</TextTemplates>

</ItemGroup>

Ths reason for this is that historically the Reaqtor codebase has used two different conventions. In some cases, the a template called, say, ByteArray.tt generates a file with the same name but a .cs template, e.g. ByteArray.cs. However, in some places the T4 includes this directive:

<#@ output extension=".generated.cs" #>

For example, that appears in the LetOptimizerTests.tt template, and the effect is that the generated file is called LetOptimizerTests.generated.cs. (In this case, that's because the generated code is adding extra methods to a partial class, so there's already a non-generated LetOptimizerTests.cs file. The generated code needs to go into a file with a different name.) Just to confuse matters further, some templates have Generated in their name, e.g. PooledObjects.Generated.tt. Obviously in this case we don't want the generated file to be PooledObjects.Generated.generated.cs, so this one is really an example of the first convention in which the .tt becomes .cs in the generated output.

The more complex XML shown above takes this into account: it looks to see if a file with that .generated.cs extension exists, and if so, selects that filename as the target for the template. But if it's not present, it just picks the other name.

Note that it's actually the template itself that determines what the output file name is with that output extension directive. This project file content just looks at what files exist, and infers from that which convention was used.

Correct Solution Explorer behaviour with DependentUpon

To ensure that the source file that a template generates appears nested inside that template in Solution Explorer, I put this in the Directory.Build.targets:

<ItemGroup>

<Compile Update="@(TextTemplates->'%(GeneratedOutputRelativePath)')">

<DesignTime>true</DesignTime>

<AutoGen>true</AutoGen>

<DependentUpon>%(TextTemplates.Filename).tt</DependentUpon>

</Compile>

</ItemGroup>

We put this in the Directory.Build.targets file so that it can run after everything in the .NET SDK's various .props files. Those will set up the Compile item group, which we just want to update. If we put this in the Directory.Build.props file, the Compile item group wouldn't exist yet so there would be nothing for us to Update.

With this in place, you can now remove all entries of this form from your project files:

<ItemGroup>

<None

Update="Example.tt"

Generator="TextTemplatingFileGenerator"

LastGenOutput="Example.cs"

/>

<Compile

Update="Example.cs"

DesignTime="True"

AutoGen="True"

DependentUpon="Example.tt"

/>

</ItemGroup>

These are no longer necessary because the preceding ItemGroup automatically sets the item group metadata correctly for all templates.

Custom target to execute templates

Finally, also in the Directory.Build.targets we define this custom target:

<Target

Name="_TransformTextTemplates"

BeforeTargets="PreBuildEvent"

Condition="@(TextTemplates) != '' and $(DevEnvDir) != ''"

Inputs="@(TextTemplates)"

Outputs="@(TextTemplates->'%(GeneratedOutputRelativePath)')">

<Exec

WorkingDirectory="$(ProjectDir)"

Command='"$(DevEnvDir)TextTransformCore.exe" "%(TextTemplates.Identity)"' />

</Target>

We've set this to execute before the PreBuildEvent, meaning that all T4 generation occurs before the main build work happens.

The Condition here ensures that this target only attempts to run when the build is in a Visual Studio environment. (Either we are using Visual Studio to run the build, or the build was run from a Visual Studio developer prompt.) This is necessary because the TextTransformCore tool is not part of the .NET SDK, so it's not universally available. It's part of Visual Studio.

Generated source files will be checked into source control, so we only ever need to run the T4 tool if the template changes. So in cases where someone just clones a repository and builds it, it won't matter if they don't have Visual Studio available because all the generated files will be present anyway. (But anyone wishing to modify a template, and to get the corresponding modified output, will need Visual Studio, because that's the only official way to get the TextTransformCore tool today.)

This target uses the Inputs and Outputs to ensure that it only runs templates when the .tt file's timestamp is newer than the generated source file. (This conditional timestamp-based execution is built into MSBuild. You just have to tell it how a target's inputs and outputs are related.)

Conclusions

We are no longer constrained to using .NET Framework inside T4 files. Although this means abandoning the built-in Visual Studio tool support, with some relatively simple project file modifications, it's possible to get your T4 files using a modern .NET runtime in a straighforward way. We do lose the ability to debug the templates, but we get automated re-execution of the templates as part of the build.