C# teamwork: share project config with common Nuget Build Asset Packages

.NET projects have pragmatic default settings, but these won't always be exactly what you want in your own projects.

For example, at endjin we like clean builds, and to remove the temptation to check in code that produces compiler warnings we configure the compiler to report errors as warnings; for legal reasons we want a copyright header in all of the open source code we publish to GitHub, so we configure StyleCop to insist on this.

We have a few policies like these that require us to deviate from the SDK's defaults. It's not that the SDK is wrong here—it would not be reasonable to impose our defaults on the rest of the world. But we do want to apply them to all of our own code.

So how can you get the defaults you want across all your projects? You can obviously just add the settings you want in every project file, but that's tedious and error-prone. The next-simplest approach is to put these settings into a file, and then add a line to every project that imports that file. This works a lot better, because it requires only a single line in each project, and it ensures that all the projects in a solution are using the same settings because those settings are defined in a single place.

You might even be able to avoid adding the <Import> line to each project file by creating Directory.Build.props or Directory.Build.targets files. If you put files with these names in the same folder as your .sln file, they will be incorporated automatically into every project, running before and after the contents of your project file respectively.

However, this approach has issues if you have multiple solutions. Endjin maintains numerous projects across various repositories, and the problem that arises with the simple "copy some files into the project" approach is that there are no good versioning or update mechanisms. What do you do if you discover that an update to the .NET SDK requires you to change something? (That's happened to us in the last week.) Or perhaps you want to introduce a new policy that requires a change to the common files.

You can go through every project and update these files by hand, but this is tedious and error-prone, and tedious and error-prone procedures are exactly what we're trying to avoid. (Are you tired of me writing "tediuos and error-prone" yet?) Moreover, when applying these kinds of updates, you discover that some projects have made their own customizations to these files, leaving you with two problems: 1) how to merge in the updates to the common files without breaking the customizations; 2) deciding whether the modifications made by this project are something you want to push out to everyone else because they are generally useful.

If only .NET had some sort of system for publishing sets of files intended for use in multiple projects in a way that supports versioning and straightforward distribution of updates…

NuGet build assets

NuGet is designed for exactly this kind of scenario. It might be used mostly for distributing DLLs, but it's perfectly capable of sharing other kinds of files. Moreover, the .NET build system has a feature designed specifically for solving the very problem at hand: a NuGet package can include files that get incorporated into your build.

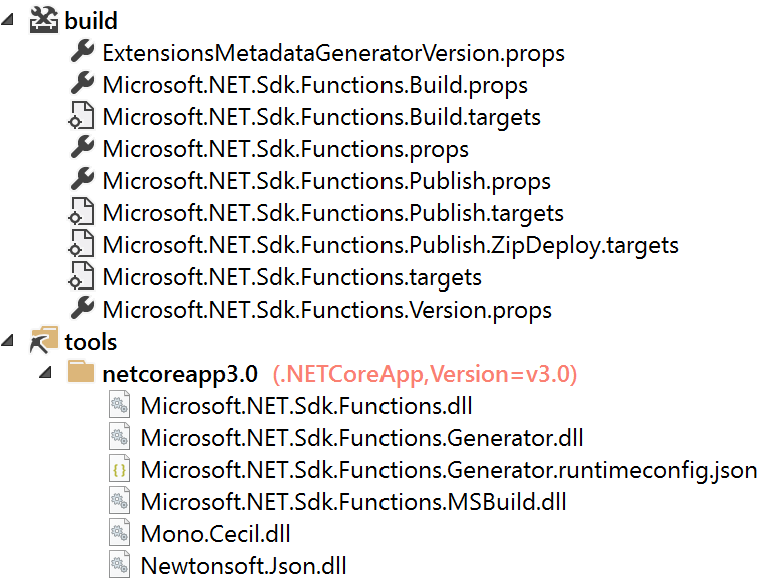

Some Microsoft packages rely on this. The Azure Functions .NET SDK needs to perform some build steps specific to Azure Functions. (For example, it needs to generate a JSON file describing each of the triggers in your code.) We can see how it's able to do this by opening up Microsoft.NET.Sdk.Functions.nupkg in the NuGet package explorer application. This is what v3.0.4 looks like:

The first thing to notice about this is that there's no lib folder. In most NuGet packages, the lib folder is the entire point of the package—we usually import NuGet packages to add some DLLs to our project, and that folder is where those DLLs live. But this package does not make any DLLs directly available to your project—all the types that support Azure Function development actually come from other packages that Microsoft.NET.Sdk.Functions.nupkg references (e.g. Microsoft.Azure.WebJobs).

This package does contain some DLLs, but they are all in the tools folder, the contents of which will not be available to your project's code; this folder is for things used at development time. These particular DLLs contain the code required to perform the extra build-time work needed in Azure Functions projects.

The presence of this tools folder does not in itself cause anything interesting to happen at build time. The most important folder here is the build folder. If a .NET project has a reference to a package that contains a build folder, the SDK will check for two files in that folder: <PackageName>.props and <PackageName>.targets (where <PackageName> is the name of the NuGet package, i.e. Microsoft.NET.Sdk.Functions in this example). Either or both may be present. The .props file, if present, will be processed before your project file's contents, and the .targets file, if present, will be processed after your project file's contents. (So these are very similar in nature to the Directory.Build.props or Directory.Build.targets files mentioned earlier, it's just that the files live in a NuGet package instead of a particular solution folder.)

You might have noticed that this example has more than those two files. How do all the other files come into play? Well the two files that the SDK picks up—Microsoft.NET.Sdk.Functions.props and Microsoft.NET.Sdk.Functions.targets—contain various <Import> elements that refer to those other ones. This seems to be a fairly common idiom: packages that do anything non-trivial during the build typically split this work into multiple files, and then the two files that the SDK goes looking for just orchestrate the execution of these other files.

The Functions SDK defines custom MSBuild tasks (e.g., for the aforementioned JSON file generation) which is why it has that tools folder, but that's not processed automatically by the .NET SDK. The Microsoft.NET.Sdk.Functions.targets file contains various <UsingTask> lines that load these DLLs explicitly: https://github.com/Azure/azure-functions-vs-build-sdk/blob/3.0.4/src/Microsoft.NET.Sdk.Functions.MSBuild/Targets/Microsoft.NET.Sdk.Functions.targets#L14-L31

If you want to see a simpler example, endijn's standard settings are up at https://github.com/endjin/Endjin.RecommendedPractices.NuGet/. Currently, we have no compiled code in this package, only .props and .targets files.

NuGet development dependencies

One thing we don't want to do is cause anyone taking a dependency on our OSS projects to end up with a dependency on our Endjin.RecommendedPractices NuGet package. (You're more than welcome to adopt them by choice, we just don't want to impose them as a condition of use!)

Normally, anything that has an explicit dependency on some NuGet package ends up with an implicit dependency on anything that package depends on. For example, our Corvus.Retry package depends on Endjin.RecommendedPractices, so you might expect that a dependency on Corvus.Retry would result in an implicit dependency on Endjin.RecommendedPractices. Not so.

The nuspec file in Endjin.RecommendedPractices includes this entry: <developmentDependency>true</developmentDependency>. This tells NuGet that nothing in this package is required at runtime—it exists purely to support development-time operations. This has the effect of disabling the normal implicit dependency behaviour, meaning you can safely add a package of this kind to your project without any impact on anyone using your project.